Recording Malcolm Arnold’s Ninth Symphony

In November 2006 Ealing Symphony Orchestra and I began a ten year concert cycle of all nine of Malcolm’s symphonies. It was an extraordinary journey for all us as we worked our way chronologically through this fascinating cycle. There were also spin-offs from this project including playing the Fourth Symphony in Cesis, Latvia and a number of appearances at the Malcolm Arnold Festival including the revival of The Dancing Master.

The Ninth Symphony lay dauntingly at the end of the journey but I had the opportunity to tackle this problematic work at the 2011 Malcolm Arnold Festival in Northampton, which celebrated Malcolm’s 90th birthday with the performance of all nine symphonies in a weekend! ESO, by this stage, had reached Symphony 6 and we presented this work alongside the revival of the Grand Concerto Gastronomique at the Saturday evening concert in the Derngate.

Paul Harris entrusted me with the Ninth symphony in the Derngate’s Sunday evening concert where I presented three pieces in reverse order to standard expectation: the Ninth Symphony in the first half, Nicola Benedetti and Leonard Elschenbroich in the Brahms Double Concerto in a second half that concluded with Tchaikovsky’s Fantasy-Overture Romeo & Juliet, all played by the Malcolm Arnold Festival Orchestra (aka Worthing Symphony Orchestra). The nature of Malcolm Arnold Festival weekends meant that some Arnold Society members missed the Sunday evening concert so only heard later about what many considered a ‘revelatory’ reading of the Ninth Symphony.

In 2015 I again programmed the Ninth Symphony in the first half of a programme – this time at the conclusion of Ealing Symphony Orchestra’s complete cycle. Again the work drew great admiration: indeed many I spoke to found it more compelling and understandable than Rachmaninoff’s Third Symphony which occupied the second half of the programme! I was not unduly surprised by this reaction. Malcolm’s music speaks with great clarity to the audience whilst the complexity of Rachmaninoff’s work was more easily appreciated by the orchestra members who had had weeks of the rehearsal process to assimilate and digest the complexity of Rachmaninoff’s last symphony.

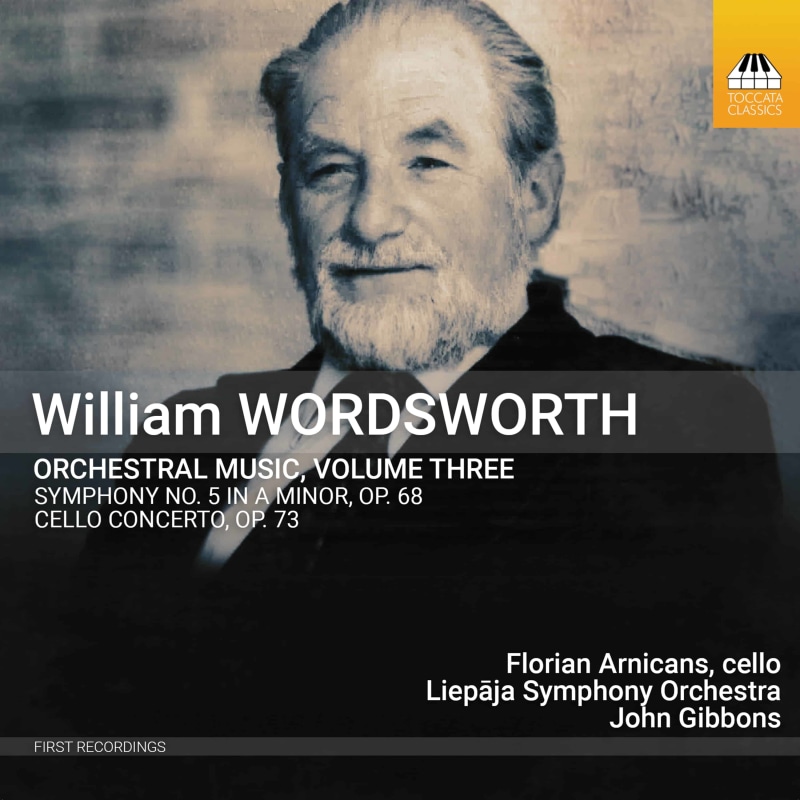

My view of Malcolm’s Ninth has now been committed to disc with the Liepaja Symphony Orchestra and has just been released by Toccata Classics. Not everyone will share my vision of the work but I was greatly heartened to receive John Pickard’s email to me on hearing the recording

It is a revelation. The work no longer sounds like ‘musical Alzheimer’s’, as someone once put it, but intensely alive, alert, vibrant and, as you say, serene. The textures no longer seem emaciated, but lean and muscular, allowing the music to cut through to the very essence, and the glowing final chord feels like the thing that the symphony has been searching for throughout its entire progress. This is all very much due to your insight and superb control of pacing and balance. It’s also a tribute to the quality of the orchestral playing. They come across as a first-class orchestra. LSO indeed!

I believe the Ninth is a misunderstood visionary work, a compelling conclusion to one of the great symphonic cycles of the twentieth century. I do not subscribe to the fashion of declaring one symphony in a composer’s cycle to be their true masterpiece. In Malcolm’s case they are all compelling and individual and are a brilliant journey through life.

Many have viewed Arnold’s Ninth Symphony as the angst ridden work of a dying man with much Mahlerian anxiety implied in the score. This contradicts my own viewpoint of the work: a view enhanced by two other late symphonies I was working on during this period; Anthony Payne’s masterly realisation of Elgar’s Third Symphony and Nors Josephson’s completion of Bruckner Nine which I recorded in 2014 with the Aarhus Symphony Orchestra on Danacord. In all three works there are dark moments of great intensity and pain but, for me, these are counter-balanced by over-riding feelings of peace and serenity; great lives that have seen and experienced the full gamut of human emotions, and are now nearing their ends. The trials and tribulations of musical acceptance are in the past, their music now for posterity to decide their value.

Malcolm’s own recordings show he was never enslaved by his own metronome markings (e.g. Commonwealth Festival Overture) so I followed ‘a pinch of salt’ approach to the last movement metronome mark, feeling the pulse as a tactus rather than a crotchet beat, and this allows the music to flow inexorably towards the sublime D major resolution at the end of the work; a process that matches my vision of the work.

The work was recorded in June 2021 with the oldest professional orchestra in the Baltic States. During Soviet times Liepaja was a closed city due to the presence of Soviet nuclear submarines and, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, a third of the population left. It now has a superb new concert hall and brilliant musicians with whom to work. They approach British music with no pre-conceived misconceptions or prejudice. They treat all the music I have recorded with them (four CDs of William Wordsworth to date) with a fresh openness and total professionalism.